blog & reflections

Growth, Borders, and the Illusion of Partnership: Lessons from the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone

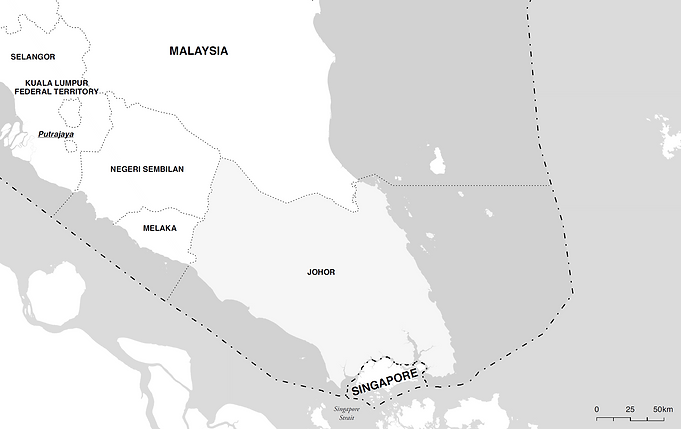

Left: Johor Bahru

Right: Singapore

I still remember the view from my plane window. I was fourteen, flying alone from Bangkok to Singapore, a trip I made almost every month. I had moved to Singapore in middle school, and at that age, I often felt homesick. The regular flights became a routine, each one just under two hours, long enough for the clouds to part and reveal the land below: a sea of rainforest, uninterrupted and identical.

From above, there were no borders, just trees, rivers and earth that looked the same across Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore. But on paper, these were three different countries, with three different economic fates. Thailand’s GDP per capita stands at $7,182.03. Malaysia’s is $11,379.07.

And Singapore? $84,734.26.

Three nations with nearly the same natural foundation, but vastly different outcomes, simply because of the invisible lines that separate them. The borders.

This window seat was my first quiet lesson in urban political economy, even if I didn’t have the words for it yet. Why do borders dictate such real-world consequences? And how do countries that sit next to each other, share cultures and histories, end up playing such different roles in the global economy?

This question stayed with me as I grew older. And in this blog, I return to it, not by comparing all three countries, but by zooming in on the fascinating relationship between Singapore and Malaysia. Specifically, I’ll look at the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone (JS-SEZ), a transnational project where both countries claim to pursue mutual benefit.

A Complicated Friendship

To navigate the dynamics between Singapore and Malaysia today, we first have to understand their complicated friendship: a relationship shaped by shared origins, political tensions and decades of uneasy interdependence.4, 12

Back in 1963, the idea of uniting Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak into a single federation seemed full of promise. Economically, culturally and geographically, it made sense. Singapore and Malaysia had deep ties dating back to the British colonial rule, when both functioned as parts of a wider imperial economy.4 But behind this seemingly strategic merger lay deep ideological divides.

On one shore, Singapore’s ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), led by Lee Kuan Yew, envisioned a meritocratic, multiracial nation where talent rose regardless of ethnicity. On the other shore, Malaysia’s ruling UMNO-led coalition upheld the “bumiputera” policy, privileging ethnic Malays in politics, education and economic redistribution. These weren’t just differences in policy, they were fundamentally different visions of what a postcolonial nation should be.4

Inevitably, tensions flared. Economic disputes over tax revenue and industrial autonomy collided with racial hostility on the ground. By 1965, the fragile union collapsed. Malaysia expelled Singapore from the Federation, an act so sudden and emotionally charged that Lee Kuan Yew broke down in tears during a national broadcast. “All my life... you see, the whole of my adult life... I have believed in merger and the unity of these two territories,” he said, visibly shaken.4

But separation didn’t mean disconnection.

Malay Peninsula

(1923)

Singapore’s Rise: From Third World to First

When Singapore was thrust into independence, few expected it to succeed. The 581.5km2 island had no natural resources, a fragmented multiethnic population, and had just lost both its economic hinterland in Malaysia and the British military bases that propped up its economy.5

Yet within a few decades, the city-state would become one of the world’s richest nations per capita.

Singapore became a textbook case of what scholars now call the developmental state, where the government plays an aggressive role in directing economic growth.18 As Katalin Völgyi notes, Singapore’s model was a rare, almost surgical form of state capitalism. The government built state-owned enterprises (SOEs), ran them like competitive business, and let them fail if they didn’t perform.18

What made Singapore exceptional wasn’t just its bureaucracy, it was its ability to move fast, plan long-term, and stay pragmatic. Singapore directed its economy toward export-oriented manufacturing, welcomed multinational corporations, and began building industrial parks, vocational programs, and ports with astonishing efficiency.5

As Lee Kuan Yew put it, “had we waited for our traders to learn to be industrialists we would have starved.” 18

Lee Kuan Yew

addresses a

crowd in 1964

Meanwhile in Malaysia: A More Complex Path

Across the strait, Malaysia’s journey followed a different rhythm. Malaysia’s path was more complicated, due to its internal diversity and scale. If Singapore moved like a speedboat, Malaysia had to steer a massive ship.9

After gaining its independence, Malaysia embarked on a series of five-year development plans. The most influential among them was the New Economic Policy (NEP) launched in 1971, which aimed to restructure society and eliminate poverty through affirmative action for the ethnic Malay majority. Though the policy did uplift millions, it also entrenched ethnic-based politics and slowed economic efficiency.9

While Singapore centralized and streamlined, Malaysia decentralized and negotiated. The country juggled between balancing growth with equity, federal autonomy with national direction, and ethnic appeasement with global competitiveness.

Still, Malaysia grew. Its economy shifted from commodities to industry and, in more recent years, toward services and the creative economy. From 1970 to the 2010s, its GDP grew sixfold, and its cities modernized rapidly.9

No place embodied this transformation more than Johor, Malaysia’s southernmost state and the closest to Singapore.

Johor and

Singapore

Diverging Goals, Shared Infrastructure

As early as the 1970s, the two countries were quietly tied together again. Both countries looked across the strait and saw opportunity, but not necessarily the same kind.12

For Singapore, the logic was clear. With limited land and a high cost of living, the city-state needed Johor as a flexible extension. Singaporeans bought cheaper homes in Johor, companies found more affordable labor, and supply chains stretched into Johor without uprooting operations. Meanwhile, thousands of Malaysian workers commuted to Singapore daily, supporting Singapore’s infrastructure, while spending their salaries back home.8

This dynamic is what scholar Aihwa Ong calls “graduated sovereignty”, a form of state power in which governments selectively open up territory to global capital, while keeping control over populations and borders.14 Singapore mastered this approach, exporting its needs without compromising its autonomy.

For Malaysia, Johor symbolized ambition. Long seen as a sleepy neighbor, the state was rebranded in the 2000s as part of Iskandar Malaysia, a master planned economic corridor modeled after Shenzhen’s rise beside Hong Kong.9 Just as Shenzhen became economically inseparable from its neighbor, Johor, too, aspired to be more than Singapore’s overflow, it wanted to be an indispensable counterpart.

Billions were poured into highways, universities, medical tourism hubs, and luxury real estate developments. These projects reflect neoliberalism as a “mobile technology”, where governing practices move across borders and adapt to local political and cultural contexts.15 In this view, neoliberalism is not a fixed doctrine, but a flexible toolkit used by states to optimize space, attract capital, and selectively engage with global markets.

On the surface, both countries claimed a win-win partnership. And in 2025, that partnership was formalized through the launch of the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone (JS-SEZ). The JS-SEZ is a landmark agreement aimed to improve cross-border connectivity, reduce investment friction, and foster joint development.11

But beneath the glossy infrastructure plans and polished MOUs, a deeper question remains. Are both countries truly working toward the same goal?

Singapore’s motivations remain anchored in control, security and economic self-preservation. Its approach to the SEZ is calculated. Malaysia, in contrast, sees the SEZ as a chance to leap forward, to attract foreign capital, prove its relevance on a global stage, and modernize Johor on its own terms.18

Coverage of

JS-SEZ

Who Gains More?

When Singapore and Malaysia promote the JS-SEZ, they often use the language of mutual gain, such as seamless connectivity, shared prosperity and cross-border collaboration.11 But in practice, the benefits of this partnership have been far from equal.

Before inking the JS-SEZ deal in 2025, Johor already recorded over $8.1 billion in property investment sales in 2007 and 2016. By 2013, over 76% of those purchases were made by foreign investors, predominantly in the high-end residential market.8

One of the flagship projects, Forest City, was launched with global fanfare, introducing a futuristic eco-metropolis built on four artificial islands. Its marketing leaned heavily on proximity to Singapore rather than on integration with Johor itself, and the majority of buyers were not locals but Chinese nationals seeking overseas property.8

Malaysia has certainly succeeded in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), and geography has a lot to do with it. Johor offers investors the benefit of being “near-Singapore” without paying Singaporean prices.13 As a key component of GDP, FDI contributes to growth by boosting exports, facilitating technology transfer, and increasing capital inflows.

In 2023, Singapore alone contributed nearly 35% of Malaysia’s total net FDI, more than any other country by a wide margin.13 As Malaysia is set to achieve high income status between 2024 and 2028, according to the World Bank, many celebrate this FDI-driver growth as a marker of national success. All this success largely stems from its location.

Net foreign direct

investment (FDI)

flows to Malaysia

in 2023, by

country

But is this growth truly reflective of self-sufficiency, or simply a reflection of Singapore’s constraints?

Johor has become home to a growing list of multinationals, including Nvidia, AirTrunk, GDS, YTL Power, and Princetown Digital Group, all of which have established data centers in the region.13 Microsoft is reportedly developing a new facility. These investments are real, but the strategic geography speaks for itself, that is, firms choose Johor not just for its incentives, but for its closeness to Singapore.

Singapore carefully maintains its role as the command center. Under its “SG+1” initiative, companies are encouraged to set up regional headquarters in Singapore while outsourcing operational functions to nearby, lower-cost areas like Johor.2

It’s a familiar model, the modern-day evolution of Hong Kong and Shenzhen, except now digitized and clad in glass.

Singapore retains control over the flow of labor, capital and data. It gains flexibility, resilience and access to land without the messiness of direct political or infrastructural entanglement.2 Even infrastructure like the upcoming Rapid Transit System (RTS) is often marketed in terms of its benefit to Singaporean commuters, just as much as Johoreans.11 Developments in Johor frequently use phrases like “just minutes from Singapore”, again, framing their value through proximity, not place.

While developers and investors profit, the social and environmental costs are largely borne by Johor’s residents.

Fishing communities were displaced. Mangroves and seagrass beds were damaged by land reclamation. Local villagers complained of exclusion from planning processes. Even the Singaporean government filed an environmental complaint. Forest City may have promised sustainability and inclusion, but to many, it became a symbol of elite exclusion, top-down urbanism and the hollow spectacle of a Chinese-built “ghost city.” 8

The growth of Johor as Singapore’s overflow has created an invisible line between winners and losers.

The winners?

Developers, foreign investors, and elite landowners.

The losers?

Middle-income Johoreans, priced out of their own neighborhoods, and commuters navigating rising costs and daily congestion.

A short

documentary by

Wall Street

Journal on

Johor’s Forest

City

The Illusion of Partnership

Singapore, with its thick wallet, global credibility, and institutional muscle, sets the pace. It defines the terms of engagement, controls key flows, and reaps the benefits of an expanded footprint. Malaysia, especially Johor, plays the part of the accommodating neighbor, welcoming capital, adjusting regulations, and offering space for everything that no longer fits in the neighboring island.2

Urban scholar Neil Brenner would call this dynamic “interlocality competition”: cities and states working together while also quietly vying for investment, legitimacy, and control over future growth. It is the collaboration underpinned by self-interest and deeply uneven power.1

And the border, rather than fading, is central to how this works.

Instead of dissolving differences, the border produces value. It enables wage differentials. It makes land in Johor “cheap” and salaries in Singapore “competitive”.8 As long as the border remains, so does the imbalance it helps sustain.

The JS-SEZ crystallizes this reality. Infrastructure is shared, but vision is not. Growth happens on both sides, but not at the same speed, or on the same terms.

While governments promote the JS-SEZ as a symbol of shared growth, consulting firms and financial institutions tend to frame it as a strategic investment instrument. KPMG’s Johor tax director describes the JS-SEZ as a “gateway to high-value industry investments”, encouraging companies to conduct feasibility studies, optimize tax exposure, and select the best flagship zones for operations.6 Maybank analysts call it a “game changer,” highlighting the zone’s ability to tap into China Plus One supply chain shifts, where global firms diversify production by expanding into Southeast Asia and beyond.13

These institutions don’t just view the JS-SEZ as a development zone. They see it as a node within a larger system of planetary urbanization, where urbanization extends far beyond city boundaries and integrates into global circuits of capital.2 In this framework, economic zones like the JS-SEZ are no longer peripheral. They become central to how capitalism reorganizes space, creating infrastructures that serve the flow of goods, data, and labor, but not always the people who live within them.10

This is not to say the partnership is fake. Investments are happening. Projects are underway. People, hundreds of thousands of them, cross the border each day to work, study, trade and live. But when we call this an equal collaboration, we risk masking the power dynamics that shape who gets what, and why.

The JS-SEZ isn’t just a zone. It’s a mirror.

It reflects how borders can act not only as barriers, but as an enabler of control, advantage and narrative dominance.

The illusion isn’t that the partnership exists. The illusion is that it’s equal.

What I Learned from the Sky

I still remember the view from that plane window, flying back and forth between Bangkok and Singapore, peering down at the landscape of trees, rivers and endless green. From the sky, there were no borders. Just land. Just Southeast Asia, flowing across lines that only exist on maps.

But as I’ve learned, those invisible lines shape everything. They determine who gets to build, who gets to commute, who gets priced out, and who gets to stay. The JS-SEZ is a bold experiment in transnational collaboration, but it’s also a reflection of how much borders still matter, even when we claim they don’t.

I didn’t write this blog out of resentment or critique. I wrote it from a place of curiosity and, in many ways, quiet envy. Despite their different approaches, Singapore and Malaysia have managed to achieve growth, secure investment, and position themselves as key players in a rapidly shifting region. That alone is worth studying, and perhaps even admiring.

Sometimes, I think about that same window seat, but instead I imagine the view crossing Cambodia into Vietnam. The land below would still look the same. And I can’t help but wonder: how would a writer from those places see my country? Would they see privilege? Inequality? Possibility? Would they write about us the same way I’ve written about Singapore and Malaysia?

Writing this blog has reminded me that not all partnerships are equal.

Not all growth is shared.

And sometimes, the view from the sky reveals more than the ground ever could.

Citations

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Brenner, N. (2013). Theses on urbanization. In Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization (pp. 85–100). Jovis Verlag.

Chua, H. B. (2022, August 17). Special economic zone talk at Forest City. Maybank Investment Bank Research.

Collier, S. J. (2009). Neoliberalism as a mobile technology. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 34(2), 137–148.

Goh, C. T. (1965). From separation of Singapore from Malaysia. Singapore National Archives.

Huff, W. G. (1994). The economic growth of Singapore: Trade and development in the twentieth century. Cambridge University Press. [Note: If this is the same content as Economic Change in Singapore, 1945–1977, confirm details.]

IRDA. (2024, August 17). Special Economic Zone Talk at Forest City. Forest City Presentation Document.

Iskandar Regional Development Authority (IRDA) & Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2025, February 3). Snapshot: Johor–Singapore Special Economic Zone (JS-SEZ).

Khoo, S. L., & Chang, N. S. F. (2021). Johor Bahru – A border city’s ideals and challenges. In Creative City as an Urban Development Strategy (pp. 137–156). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-1291-6_8

Lee, C., & Lee, C.-G. (2017). The evolution of development planning in Malaysia. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 34(3), 436–461. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44685075

Merrifield, A. (2014). The new urban question (Chapter 1). Pluto Press.

Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry Malaysia (MITI) & Iskandar Regional Development Authority (IRDA). (2024, February 3). Snapshot: Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone (JS-SEZ). https://www.miti.gov.my​:contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

Nathan, K. S. (2002). Malaysia–Singapore relations: Retrospect and prospect. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 24(2), 385–410. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25798602

Ng, F. L. (2025, March 31). Unlocking strategic investment opportunities in the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone. The Edge Malaysia. Retrieved from your uploaded PDF titled: the-edge-ng-fie-lih-investment-opportunities-js-sez-31-march-2025.pdf

Ong, A. (2000). Graduated sovereignty in South-East Asia. Theory, Culture & Society, 17(4), 55–75.

Ong, A. (2007). Neoliberalism as a mobile technology. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 32(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00234.x

Pillai, S. (1990). Foreign labor and economic development in Singapore. Singapore University Press.

Singapore Department of Statistics. (1977). Economic change in Singapore, 1945–1977. Singapore Government Press.

Völgyi, K. (2019). A successful model of state capitalism: Singapore. In M. Szanyi (Ed.), Seeking the best master: State ownership in the varieties of capitalism (Chapter 10). Central European University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctv138wqt7.13​:contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

Wong, L. L. (1983). Foreign labor and economic development in Singapore: A policy-oriented approach. International Migration Review, 17(4), 712–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838301700402​:contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}